No time to read? Listen to the podcast.

If Dorothy had landed in Manhattan instead of Oz she still would have known she was far from home, even with her eyes closed. All she had to do was wait for someone speak.

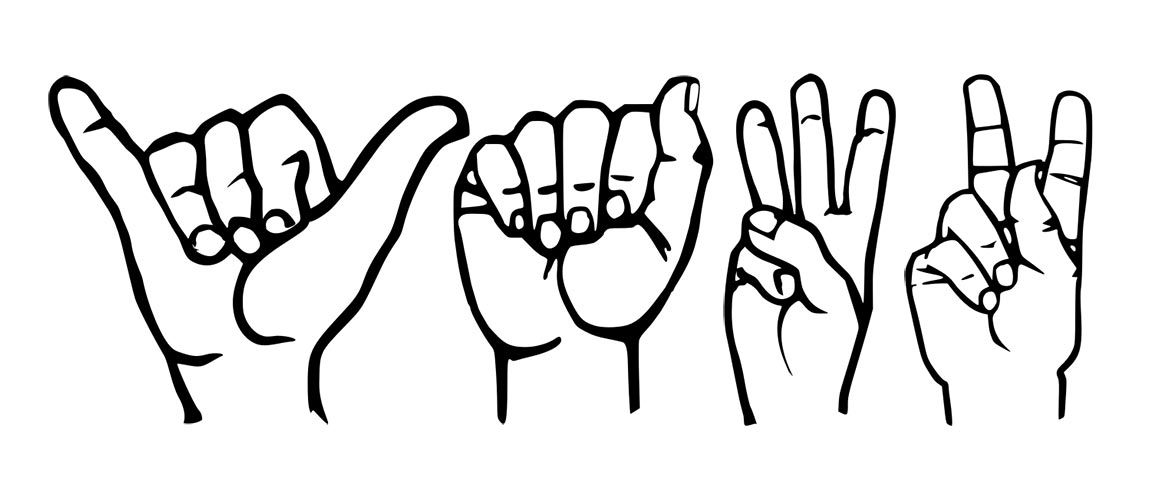

Then again, she could have figured it out with her eyes open if she’d known a little bit of American Sign Language (ASL).

It seems it’s not only spoken English that comes with that world-famous New York accent. Deaf New Yorkers communicating in ASL may have New York accents as well. And deaf non-New Yorkers often have the same challenges understanding that accent as hearing people do.

“Hearing New Yorkers have different gestural mannerisms than people from other parts of the country. You might see deaf New Yorkers incorporate those mannerisms into their signing. ”

It’s not that deaf New Yorkers use totally different signs. There’s no sign for “coffee” and another one for “cawfee,” for example. But to understand what’s going on you need to get past all that nonsense you learned watching westerns.

Those scenes in the westerns of the 1950s, with their oversimplified gestures for sun, moon, and white man speaks with forked tongue, were cheap theatrical stunts.

ASL is nothing like that. Its roots trace back not to the Wild West but to Gay Paree.

In 1817, Yale graduate Thomas Gallaudet, and his former student, Laurent Clerc, opened the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. Gallaudet was inspired by the teaching methods at the French Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, and ASL was his method for communicating with his deaf students. ASL, like spoken French—or English or Japanese—was, and is, a natural language. As such, it has its own lexicon; grammatical rules; ways of expressing possession and tense; and even style.

And when a language has a style, accents are not far behind.

“New Yorkers are notorious fast-talkers, while Ohioans are calm and relaxed,” wrote Olivia Goldhill at the Gizmodo blog. As it turns out, so are those regions’ ASL accents.

According to Goldhill, ASL accents can be extreme “to the point where the signs are not able to be deciphered based on what they look like. People say, ‘Oh…you sign strange.’”

Imagine getting directions to toity-toid-n-toid from a third-generation New York policeman. An ASL New York accent isn’t quite that bad, but it can be challenging.

You also have to get past the idea that ASL is a collection of little pictures or movements made by the hands. There are five components to ASL: hand shape; hand location; hand movement, for example side to side; palm direction, toward or away from the signer; and facial expression.

Any and all can vary when the signer has an accent. Or, as Dr. Casey Thornton, adjunct professor of deaf studies at California State University, Northridge, prefers to call them, variations.

“Accents refer to the pronunciation of a word. In signed languages the changes are visible rather than auditory,” she said.

Variations, like accents, arise when groups of people from different environments develop their own ways of signing.

“Sometimes a person wants to show her identity as part of a community or culture,” Dr. Thornton said. ”That’s a conscious or unconscious choice.”

In the case of a New York ASL accent, those variations may arise when deaf signer wants to identify with the New York Deaf culture.

“Sometimes the variation is historical, gender-related, or political,” according to Dr. Thornton. “When deaf students were segregated by race they developed different ways of signing.”

Another factor, suggested Dr. Thornton, is the general New York City culture. “Hearing New Yorkers have different gestural mannerisms than people from other parts of the country. You might see deaf New Yorkers incorporate those mannerisms into their signing. That would become part of a ‘New York accent’ even though the language, itself, didn’t change.”

Accents and variations may be charming, but Dr. Thornton cautioned not “…to make judgments about people based on the language they’re using.”

It’s true. I had an aunt and uncle who spoke Yiddish at home. They could be having sex but they still sounded as if they were threatening domestic violence (or so I’m told).

“When variations within a language are the target of ridicule or misunderstanding, making judgments based on them can be very detrimental,” Dr. Thornton said.

Which means a deaf New Yorker who signs more rapidly and vigorously than her Georgia cousin could be as kind and considerate underneath as a hearing New Yorker who greets you with, “Hey, dis is Nu Yawk so get outta my face.”

Then, again…

Nevertheless, whether ordering a knish or telling the story of three guys who walked into a Lower East Side bar, a deaf New Yorker’s hands can be one more sign you’re not in Kansas any more.

Start your Sunday with a laugh. Read the Sunday Funnies, fresh humor from The Out Of My Mind Blog. Subscribe now and you'll never miss a post.

Dr. Casey Thornton is an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Deaf Studies at California State University, Northridge (CSUN). After completing her Bachelors Degree in Deaf Studies from CSUN in 2009, she continued her studies at Gallaudet University in Washington D.C. She received her M.A. degree in Linguistics in 2012 and her Ph.D. in 2017. Dr. Thornton’s research interests include universal phonotactic constraints in signed languages and bridging gaps between theoretical models of phonology and linguistic experimentation. When not working she enjoys spending time with her family playing board games.

Mind Doodle…

There are seven signs for computer in ASL, including one in which both hands make spinning motions. The sign dates back to 1960s IBM computers, which used huge reels of magnetic tape that spun while the computer was working.

I taught my baby son how to sign. At ten months he signed ‘milk’ and then rapidly learned many more signs. It was incredible how this helped him communicate and relieve frustration. He didn’t cry much because he could tell us his needs.

Hi Morgan…

That’s so cool. I came across that in my research…teaching babies to sign to reduce their frustration over lack of communications skills. Is there a Canadian Sign Language or does Canada also use ASL? Is there a Canadian “accent?”

— jay

Posted on Facebook.

Hi Nancy…

Thank you.

i see it as a good sign 🙂